Hope for the best and prepare for the worst is an old phrase, largely attributed to Disraeli. It sounds like sensible advice but do people really take time to ‘prepare for the worst’ given that the failure rate for projects is spectacularly high.

So how do we mitigate against failure?

How do we reduce the likelihood of it happening?

There are a number of ways in which we can practically do this and I would like to share two with you now.

The first is a process known as a Pre-Mortem.

The following is an extract from an HBR article which explains the concept better than I could..

A pre-mortem is the hypothetical opposite of a post-mortem. A post-mortem in a medical setting allows health professionals and the family to learn what caused a patient’s death. Everyone benefits except, of course, the patient. A pre-mortem in a business setting comes at the beginning of a project rather than the end, so that the project can be improved rather than autopsied. Unlike a typical critiquing session, in which project team members are asked what might go wrong, the pre-mortem operates on the assumption that the “patient” has died, and so asks what did go wrong. The team members’ task is to generate plausible reasons for the project’s failure.

A typical pre-mortem begins after the team has been briefed on the plan. The leader starts the exercise by informing everyone that the project has failed spectacularly. Over the next few minutes those in the room independently write down every reason they can think of for the failure—especially the kinds of things they ordinarily wouldn’t mention as potential problems, for fear of being impolitic. For example, in a session held at one Fortune 50–size company, an executive suggested that a billion-dollar environmental sustainability project had “failed” because interest waned when the CEO retired. Another pinned the failure on a dilution of the business case after a government agency revised its policies.

Next the leader asks each team member, starting with the project manager, to read one reason from his or her list; everyone states a different reason until all have been recorded. After the session is over, the project manager reviews the list, looking for ways to strengthen the plan.

Although many project teams engage in prelaunch risk analysis, the pre-mortem’s prospective hindsight approach offers benefits that other methods don’t. Indeed, the pre-mortem doesn’t just help teams to identify potential problems early on. It also reduces the kind of damn-the-torpedoes attitude often assumed by people who are overinvested in a project. Moreover, in describing weaknesses that no one else has mentioned, team members feel valued for their intelligence and experience, and others learn from them. The exercise also sensitizes the team to pick up early signs of trouble once the project gets under way. In the end, a pre-mortem may be the best way to circumvent any need for a painful post-mortem.

A pre-mortem puts a team in the future and gets them to look back at the likely risks which will lead to failure. It engages the power of hindsight – but from a position where you can do something about it. It’s relatively simple process that should be in the toolbox of any project manager.

The second tool is a process known as Wargaming.

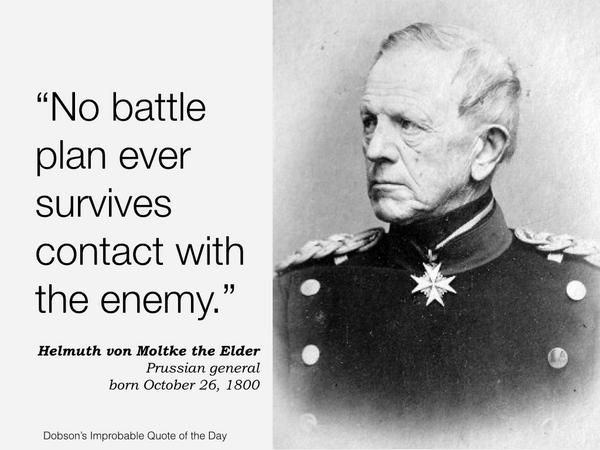

Everyone who has served in the military will have heard this. The modern version is Eisenhower’s, ‘In preparing for battle, I have always found that plans are useless but planning is indispensable’.

We understand and accept that the enemy has a part to play in whatever we choose to do.

We accept that fact. We cannot control the outcome – we can only control the quality of the input.

So we strengthen our plans by testing them in a safe environment. We mitigate the risk by going through the plan in detail and providing an opposing team with an opportunity to ‘critique’ it or say what they would do ‘if we followed this course of action’.

In the commercial world, plans are built to take into account market conditions, stakeholder behaviour and various other factors in great detail. However, the plans are built with the current situation in mind. If the situation changes, the plan often struggles to adapt.

Wargaming helps to take into account the future dynamics that might impact the plan. It allows you to simulate how conditions will develop over time as well as assessing your stakeholder’s reactions to your moves.

The process applies a level of ‘controlled pressure’ to the planning team – but in a safe environment. It significantly increases the likelihood of a plan’s success and if you’re going to invest millions of pounds in doing something – wouldn’t it be sensible to make sure the plan lasts longer than a month?

If you’re interested in Business Wargaming and want to see what it can do for your business, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with Chris Paton of Quirk Solutions and ask him to talk you through the process in more detail. It is now an essential process for some of the largest commercial plans in the UK.

If you can’t afford for your plan to fail – it might be worth dropping him a line.